Quadratojugal bone Contents Evolution References Navigation menuThe tree of life: a phylogenetic classificationFeeding: Form, Function and Evolution in Tetrapod Vertebrates10.1002/ar.235121932-84942800040910.1007/s12549-014-0182-81867-1608"Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia"10.1073/pnas.17067521141091-6490550265028630337"Early tetrapod relationships revisited"10.1017/S14647931020061031280342310.1671/039.029.011210.1080/00222934608654599"The evolution of the jaw articulation of cynodonts""Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution"10.1038/nature062771476-46871807558010.1007/s00114-003-0461-01432-19041456440810.1002/ar.234461932-849428000410

Vertebrate anatomy

cranialbonetetrapodsjugalsquamosalquadrate bonereptilesamphibianssalamandersmammalsbirdssquamateslizardssnakesSarcopterygiiplacodermactinopterygiianshomologouscoelacanthsonychodontsPorolepiformeslungfishpreoperculumtetrapodomorphElpistostegaliansmaxillaReptiliomorphareptilessalamandersMiocenecaecilianTriassicstereospondyllysorophiansPaleozoicmicrosaurssynapsidsevolutioneothyrididscaseidstherapsidsgorgonopsianstherocephaliansdicynodontscynodontmammaliaformsstapesincusmiddle earSauropsidsdiapsidsinfratemporal fenestraanapsidPermiantanystropheidsthalattosaurspistosaursplesiosaursIchthyosaurspostorbital boneturtlesrhynchocephalianstuataraArchosauriformescrocodiliansdinosaursplacodontsrhynchosaurschoristoderesNeoavesavialans

The quadratojugal is a cranial bone that is present in many tetrapods and their close relatives.[1] It forms the rear lower corner of the skull, typically connecting to the jugal (cheek bone) from the front and the squamosal from above. The inner face of the quadratojugal also connects to the quadrate bone which forms the cranium's contribution to the jaw joint. Many living and extinct reptiles and amphibians possess a quadratojugal, but the bone has been lost or fused to other bones in several lineages. Modern examples of tetrapods without a quadratojugal include salamanders, mammals, birds, and squamates (lizards and snakes).[2]

Contents

1 Evolution

1.1 Origin

1.2 Synapsids

1.3 Sauropsids

2 References

Evolution

Origin

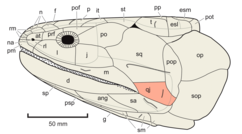

The skull of the tetrapodomorph fish Eusthenopteron, with the quadratojugal (red) labelled.

The quadratojugal likely originated within the clade Sarcopterygii, which includes tetrapods and lobe-finned fish. Although a tiny bone similar in position to the quadratojugal has been observed in the placoderm Entelognathus and some early actinopterygiians (Mimipiscis, Cheirolepis), it is unclear whether this bone was homologous to the quadratojugal. A quadratojugal is absent in actinians (coelacanths) and onychodonts, but it was clearly present in Porolepiformes, distant relatives of modern dipnoans (lungfish). Many paleontologists argue that the quadratojugal was formed by a division of the preoperculum, although a few believe that it was present before the preoperculum formed. All tetrapodomorph fish had a quadratojugal, retained by their tetrapod descendants. Elpistostegalians such as Panderichthys, Tiktaalik, and other very tetrapod-like fish were the first vertebrates to have contact between the quadratojugal and jugal. Before the elpistostegalians, the jugal was small and isolated from the quadratojugal by the squamosal and maxilla.[3]

Amphibians (in the broad sense) typically had long, roughly rectangular quadratojugals that contacted the maxilla, jugal, squamosal, and quadrate. In several lineages, most of them traditionally considered "Reptiliomorpha", the jugal expands downwards to reduce the amount of contact between the quadratojugal and maxilla. This is exemplified in reptiles, which have completely lost the contact. Most urodelans (salamanders) lack quadratojugals, except the Miocene genus Chelotriton.[4] A quadratojugal is also missing in the caecilian-like Triassic stereospondyl Chinlestegophis[5] as well as the lysorophians, a group of long-bodied Paleozoic microsaurs. Many other microsaurs had heavily reduced quadratojugals.[6]

Synapsids

The skull of Gorynychus, a therocephalian synapsid. The tiny quadrate-quadratojugal complex is labelled with q-qj.

In synapsids (mammals and their extinct relatives), the quadratojugal undergoes significant transformation during the evolution of the group. Early synapsids such as eothyridids and caseids retained long quadratojugals and in some cases even reacquire quadratojugal-maxilla contact.[7] In most therapsids, including gorgonopsians, therocephalians, and dicynodonts, the quadratojugal is tiny, having lost its contact with the jugal. It usually fuses with the equally small quadrate to form the quadrate-quadratojugal complex.[8] Oddly enough, the cynodont Thrinaxodon retains a separate quadratojugal. In other cynodonts such as Cynognathus, the quadrate-quadratojugal complex remains hidden within the skull, obscured from the side by the large squamosal bone which loosely articulates with it.[9] The most "advanced" cynodonts, including the mammaliaforms, have lost the quadratojugal, with the diminutive quadrate connecting to the stapes to function as a hearing structure. In mammals, the quadrate is known as the incus, or anvil bone of the middle ear.[10]

Sauropsids

Sauropsids, the group containing reptiles and birds, had completely lost the contact between the quadratojugal and maxilla. In diapsids, the quadratojugal and jugal form the lower temporal bar, which defines the lower border of the infratemporal fenestra, one of two holes in the side of the head. In early diapsids such as Petrolacosaurus and Youngina, the quadratojugal is long as in amphibians, early synapsids, and "anapsid" reptiles. It forms most of the length of the lower temporal bar. However, significant transformation of the temporal region of the skull occurs in many more "advanced" members of Diapsida, with implications for the structure of the quadratojugal.[11]

The skull of Prolacerta, a relative of the Archosauriformes with an incomplete lower temporal bar. The small, crescent-shaped quadratojugal is labelled with 153-0.

Numerous diapsids have an incomplete lower temporal bar, where the quadratojugal and jugal fail to contact each other. This leaves the infratemporal fenestra with an arch-like structure, open from below. An incomplete (or absent) lower temporal bar is first seen in the Permian genus Claudiosaurus, and is retained by most other Permian and Triassic diapsids. In many cases, the quadratojugal is lost completely. This loss occurs in several Triassic marine reptiles such as tanystropheids, thalattosaurs, pistosaurs, and plesiosaurs. Squamates, the group containing modern lizards and snakes, also lack a quadratojugal, but early squamate relatives such as Marmoretta do retain the bone. Ichthyosaurs, a group without a lower temporal bar, have a quadratojugal that is taller than it is long, stretching above (rather than below) the open infratemporal fenestra to contact the postorbital bone (rather than the jugal). Early turtles such as Proganochelys also have a tall quadratojugal, which contacts the jugal without any trace of the infratemporal fenestra.[11]

The skull of the dromaeosaurid dinosaur Dromaeosaurus, with the quadratojugal (light blue) labelled.

Several Triassic reptiles reacquire the lower temporal bar, albeit with the jugal forming most of the bar's length. In these reptiles, the quadratojugal is a small L- or T-shaped bone at the rear edge of the skull. Although early rhynchocephalians such as Gephyrosaurus have an incomplete lower temporal bar and a quadratojugal fused to the quadrate, later members of the group such as the modern tuatara (Sphenodon) do have a complete lower temporal bar, albeit with the quadratojugal still fused to the quadrate. All members of the group Archosauriformes, which contains archosaurs such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, have a complete lower temporal bar. This is also the case in placodonts, Trilophosaurus, some rhynchosaurs, and choristoderes.[11]

Modern birds (Neoaves) have a quadratojugal which is assimilated into the thin, splint-like jugal. However, a separate quadratojugal is retained by several Mesozoic avialans, such as Archaeopteryx and Pterygornis. Non-avialan dinosaurs also have a separate quadratojugal.[12]

References

^ Lecointre, Guillaume; Le Guyader, Hervé (2006). The tree of life: a phylogenetic classification. Harvard University Press, 2006. p. 380. ISBN 9780674021839. Retrieved December 10, 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ Schwenk, Kurt (2000). Feeding: Form, Function and Evolution in Tetrapod Vertebrates (1st ed.). Academic Press. p. 537. ISBN 9780080531632. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

^ Gai, Zhikun; Yu, Xiaobo; Zhu, Min (January 2017). "The Evolution of the Zygomatic Bone From Agnatha to Tetrapoda". The Anatomical Record. 300 (1): 16–29. doi:10.1002/ar.23512. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 28000409.

^ Kupfer, Alexander; Poschmann, Markus; Schoch, Rainer R. (2015-03-01). "The salamandrid Chelotriton paradoxus from Enspel and Randeck Maars (Oligocene–Miocene, Germany)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 95 (1): 77–86. doi:10.1007/s12549-014-0182-8. ISSN 1867-1608.

^ Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Small, Bryan J.; Pardo, Jason D. (2017-07-03). "Stem caecilian from the Triassic of Colorado sheds light on the origins of Lissamphibia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (27): E5389–E5395. doi:10.1073/pnas.1706752114. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5502650. PMID 28630337.

^ Marcello Ruta, Michael I. Coates and Donald L. J. Quicke (2003). "Early tetrapod relationships revisited" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 78 (2): 251–345. doi:10.1017/S1464793102006103. PMID 12803423.

^ Reisz, Robert R.; Godfrey, Stephen J.; Scott, Diane (2009). "Eothyris and Oedaleops: do these Early Permian synapsids from Texas and New Mexico form a clade?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1671/039.029.0112.

^ Parrington, F.R. (1946). "LXXIV.—On the quadratojugal bone of synapsid reptiles". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (107): 780–786. doi:10.1080/00222934608654599.

^ Crompton, A.W. (1972). "The evolution of the jaw articulation of cynodonts". Studies in Vertebrate Evolution. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. pp. 231–251.

^ Luo, Zhe-Xi (13 December 2007). "Transformation and diversification in early mammal evolution" (PDF). Nature. 450 (7172): 1011–1019. doi:10.1038/nature06277. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 18075580.

^ abc Müller, Johannes (2003-10-01). "Early loss and multiple return of the lower temporal arcade in diapsid reptiles". Naturwissenschaften. 90 (10): 473–476. doi:10.1007/s00114-003-0461-0. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 14564408.

^ Wang, Min; Hu, Han (2017-01-01). "A Comparative Morphological Study of the Jugal and Quadratojugal in Early Birds and Their Dinosaurian Relatives". The Anatomical Record. 300 (1): 62–75. doi:10.1002/ar.23446. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 28000410.